L.V Tarasov Summary - Part 1

L.V Tarasov- Calculus Summary - Part 1

Calculus has never been so easy and interpretable before this wonderful text of Calculus- Basic Concepts for High School by L.V Tarasov. I am documenting the summary of each Dialogue(Lesson) to keep it handy for any future revisions. Also, it will be helpful for people who wants to have a quick understanding of these topics nevertheless I would always recommend reading the text for the first time over the summary if time is not a constraint.

I will be covering three dialogues in a blog and continue the series.

Dialogue 1 - Infinite Numerical Sequence

Any infinite sequence has an infinite number of terms. Like 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, … or 2, 0, −2, −4, −6, −8, −10, −12, …. In the above infinite sequences, the terms follow a certain law. But what about the other infinite sequence which does not follow a mathematical law? Or is there any such sequence that comes under this category?

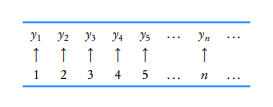

The first definition of an infinite series as stated by the author is

“ We say that there is an infinite numerical sequence if every natural number (position numbers is unambiguously placed in correspondence with a definite number ( term of the sequence) by a specific rule.”

Here \(y_n\) is the \(n^{th}\) term of the sequence. For example in the sequences stated above we have

\[y_n = 2^n ; y_n=4-2n\]The \(n^{th}\) term here follows a certain mathematical equation. But even if the \(n^{th}\) term of the sequence don’t follow an analytical expression we can still call some series as “Infinite Numerical Series”. For instance

- 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23,…

- 3, 3.1, 3.14, 3.141, 3.1415, 3.14159,…

Here we have the first as the sequence of prime numbers and second as a sequence composed of decimal approximations, with deficit, for π.

So a infinite numerical sequence can either be by the formula for the \(n^{th}\) term or by the recurrence relation. There is no superior or inferior in such sequences.

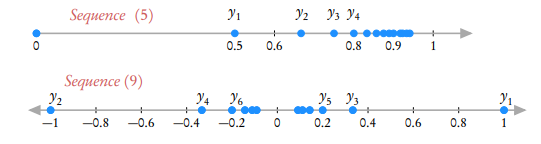

If we plot the sequences in a number line then we can see increasing or non-decreasing as well as decreasing or non-increasing sequences which are collectively termed as monotonic. However, we also have sequences which do not follow any monotonic behavior (neither increasing nor decreasing).

Here sequence (5) is monotonic and sequence (9) is not.

There is another categorization i.e. of a bounded sequence.

A sequence \(y_n\) is bounded if there are two numbers A and B labeling the range which encloses all the terms of a sequence A ⩽ \(y_n\) ⩽ B (n = 1, 2, 3, …).

The sequence (9) is not monotonic and seems to be bounded between -1 and 1. However, we can also say it is bounded between -100 and 100.

Similarly we have sequences which are monotonic but bounded. Thus we can’t always say that an increasing series will lead to infinity. A dynamic rate of increase/increments with each term can also make a sequence bounded instead of pulling it towards infinity.

We can have all the combinations of monotonicity and boundedness in the infinite sequences.

The presence of both the monotonicity and boundedness is something not so simple to understand and here’s where limit steps in.

Dialogue 2 - Limit of Sequence

Let’s start with the official rigorous definition by the author

| “The number a is said to be the limit of sequence ( \(n^{th}\) ) if for any positive number ϵ there is a real number N such that for all n > N the following inequality holds: $$ | y_n - a | <ϵ$$ “ |

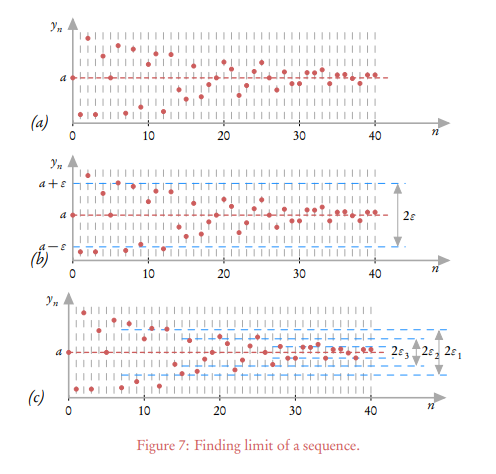

In Figure 7 (a) , a sequence is plotted in an x-y plane. Now we take any positive number, ϵ and layoff on the y-axis an interval of length ϵ, both upward and downward from the same point a. Now we draw through the points y = a + ϵ and y = a − ϵ the horizontal straight lines that mark an “allowed” band for our sequence. For this band there if there exists a positive number n = N, after which all \(n^{th}\) terms of infinite tail falls within the allowed band (or mathematically \(|y_n - a|<ϵ\) ) , then a is the limit of the sequence. In Figure 7(c) three situations are drawn up for \(ϵ_1\) ,\(ϵ_2\) and \(ϵ_3\). Correspondingly, three “allowed” bands are plotted on the graph. For a greater clarity, each of these bands has its own starting N. We have chosen \(N_1\) = 7, \(N_2\) = 15, and \(N_3\) = 27. After these N all the remaining terms of the sequence( their number is infinite) do stay within the band.

This is the concept of Limits. We can solve the limit sums by a variety of methods(to be discussed later) but we surely get the essence of limits by the broad discussion already done.

Dialogue 3 - Convergent Sequence

This dialogue has a series of theorems which are directly derived from the concept of limits. Derivations can be referred from the book directly.

- If a sequence has a limit, it is bounded. If the sequence has a limit, there exist two numbers A and B such that A⩽ \(y_n\) ⩽ B for each term of the sequence(both finite and infinite). In conclusion for an infinite set, in the interval from a − ϵ to a + ϵ we have an infinite set of \(y_n\) starting from n = N + 1 so that outside of this interval we shall find only a finite number of terms (not larger than N ).

- The boundedness of a sequence is a necessary condition for its convergence; however, it is not a sufficient condition. If a sequence is convergent, it is bounded. If a sequence is unbounded, it is definitely non-convergent,

- Weierstrass Theorem: If a sequence is both monotonic and bounded, it is a sufficient (but not necessary) condition for its convergence.

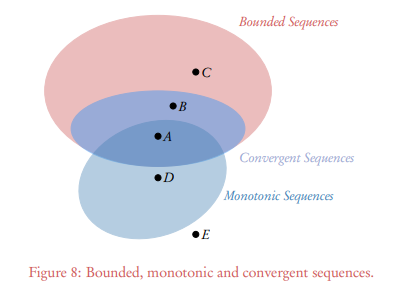

Conclusions from the figure:

- Any convergent sequence must be also bounded.

- Any sequence that is both bounded and monotonic must be convergent as well.

-

A - Sequence that is bounded, monotonic and convergent i.e if a sequence is both bounded and monotonic it is definitely convergent.

B - Sequence that is bounded and convergent i.e all convergent sequence are bounded

C - Bounded sequence which is not convergence

D - Monotonic Sequence which is unbounded and thus not convergent

E - neither monotonic nor convergent nor bounded.

- There can be no bounded, monotonic, and non-convergent sequence.

- it is impossible to have both unboundedness and convergence in one sequence.

- Uniqueness of the limit : A convergent sequence has only one limit.

- If sequences (\(y_n\)) and ( \(z_n\)) are convergent (we denote their limits by a and b, respectively), a sequence ( \(y_n + z_n\)) is convergent too, its limit being a + b.

- If a sequence ( \(y_n + z_n\)) is convergent, two alternatives are possible:

- sequences (\(y_n\)) and ( \(z_n\)) are convergent as well, or

- sequences ( \(y_n\)) and ( \(z_n\)) are divergent.

- Infinitesimal sequence: A convergent sequence with a limit equal to zero.

- If (\(y_n\)) is a bounded sequence and (\(a_n\)) is infinitesimal, then ( \(y_na_n\)) is infinitesimal as well.

- A sequence ( \(y_nz_n\)) is convergent to ab if sequences ( \(y_n\)) and ( \(z_n\)) are convergent to a and b, respectively.

- If (\(y_n\)) and (\(z_n\)) are sequences convergent to a and b when b ̸= 0, then a sequence \(y_nz_n\) is also convergent, its its limit being \(a/b\).

- Elimination, addition, and any other change of a finite number of terms of a sequence do not affect either its convergence or its limit (if the sequence is convergent).

- If an initial sequence is convergent, an elimination of an infinite number of its terms (provided that the number of the remaining terms is also infinite) does not affect either convergence or the limit of the sequence. If, however, an initial sequence is divergent, an elimination of an infinite number of its terms may, in certain cases, convert the sequence into a convergent one. For example

Turns into

\[1, \frac{1}{3}, \frac{1}{5},\frac{1}{7},\frac{1}{9},\frac{1}{11}........\]We can also break one convergent series into two or three convergent series and even spoil a convergence with slight manipulation.